Let us say grace, as it were. The 60s are beguiling. I don’t mean the 1960s. I was born in 1959 and couldn’t say “permissive society” back then, let alone live it. I mean being in my 60s, an age that seems, so far at least, to be dramatically different from its younger sibling. In my 50s I was just a mature adult, not especially different from what I’d been before. Now, just turned 63, I consider mortality, think about pensions, look at obituaries to see how old the deceased were, consider how old my heroes were when they died (often younger than I am now) and bathe in memory and nostalgia. And few things trigger thoughts of times past as vehemently as food.

Back to those not so permissive 1960s. My dad was a London cab driver—Jewish, as so many cabbies were, and from rough, wonderful Tottenham. That meant being a Spurs fan, and when I was a child he took me along to home games every second Saturday, and to few local away ones.

Back to those not so permissive 1960s. My dad was a London cab driver—Jewish, as so many cabbies were, and from rough, wonderful Tottenham. That meant being a Spurs fan, and when I was a child he took me along to home games every second Saturday, and to few local away ones.

After the games, as the splendid green of Tottenham’s holy fields faded into the cloak of dusk, we would drive to my grandparents, Dad’s mum and dad, for Shabbos dinner. Not Shabbat. We were Ashkenazi and this was before the Israeli pronunciation of Hebrew became dominant in the diaspora. Shabbos. We weren’t at all religious, proven by the fact that we’d been driving to watch football.

If my dad had a rabbi, he wore a white shirt and blue shorts, and these Sabbath dinners should really have been on Friday rather than Saturday evenings. Post-sabbath, so to speak. For me it was even more confusing, because I was the product of a mixed marriage. So, it wasn’t religion as such, but it was faith. Family, friendship, tradition, culture, community. Faith.

There, in this little apartment in Hackney I’d sit down to a feast that seemed as foreign to me as West Ham or Chelsea. I was British all through. Bacon-eating, milk-and-meat-mixing, non-Kosher-consuming British. Yet here on Saturday nights I’d be taken to the dining rooms of Odessa, to gefilte fish, chicken soup with matzo balls (we called it kneidlach), brisket, roasted chicken, and latkes. Not at all the Mediterranean Diet but very much eastern European. Spend any time in Ukraine or Russia and you realize that much of Ashkenazi cuisine is as Slavonic as it is Jewish.

There would be prayers over the wine and the bread, and then the game would start. Not the referee’s whistle but something rather similar in a way. I can’t claim that fine wines were drunk, or that the food was even especially good. That, however, isn’t really the point. It’s not the quality of the table but that there was family seated around that table. A people whose recent ancestors had fled pogroms and oppression, who had lost so many in those regular slaughters and then in the genocidal filth of the Shoah, sat in safety and pushed up their cholesterol count along with those they loved and trusted. That was—yes—faith at is finest. Somehow, God knows how, they had survived history. Yes, God did and does know.

Now, half a century later I sit in my large, warm, comfortable Toronto home and consume a much more delicate and subtle meal. Nuance, spices, delicate balances of flavour. And I’m no longer a little boy but a successful journalist and an ordained priest in the Anglican Church. Good Lord that would have surprised them all back then. But made them proud too; well, to be candid, some of them, and some of what I am.

But food is food, and one of the links in the chain of organized goodness and communal kindness is food and family and faith. My grandparents are gone now of course, as are my parents, and their siblings—even my dad’s brother who played for Tottenham reserves. Gone but not forgotten in my 60s memory and in my 60s love. “Let the boy eat,” my grandma used to say about me to my dad. Yes, let us all eat. It’s a matter of faith. Thank God.

A Matter of Faith

Let us say grace, as it were. The 60s are beguiling. I don’t mean the 1960s. I was born in 1959 and couldn’t say “permissive society” back then, let alone live it. I mean being in my 60s, an age that seems, so far at least, to be dramatically different from its younger sibling. In my 50s I was just a mature adult, not especially different from what I’d been before. Now, just turned 63, I consider mortality, think about pensions, look at obituaries to see how old the deceased were, consider how old my heroes were when they died (often younger than I am now) and bathe in memory and nostalgia. And few things trigger thoughts of times past as vehemently as food.

After the games, as the splendid green of Tottenham’s holy fields faded into the cloak of dusk, we would drive to my grandparents, Dad’s mum and dad, for Shabbos dinner. Not Shabbat. We were Ashkenazi and this was before the Israeli pronunciation of Hebrew became dominant in the diaspora. Shabbos. We weren’t at all religious, proven by the fact that we’d been driving to watch football.

If my dad had a rabbi, he wore a white shirt and blue shorts, and these Sabbath dinners should really have been on Friday rather than Saturday evenings. Post-sabbath, so to speak. For me it was even more confusing, because I was the product of a mixed marriage. So, it wasn’t religion as such, but it was faith. Family, friendship, tradition, culture, community. Faith.

There, in this little apartment in Hackney I’d sit down to a feast that seemed as foreign to me as West Ham or Chelsea. I was British all through. Bacon-eating, milk-and-meat-mixing, non-Kosher-consuming British. Yet here on Saturday nights I’d be taken to the dining rooms of Odessa, to gefilte fish, chicken soup with matzo balls (we called it kneidlach), brisket, roasted chicken, and latkes. Not at all the Mediterranean Diet but very much eastern European. Spend any time in Ukraine or Russia and you realize that much of Ashkenazi cuisine is as Slavonic as it is Jewish.

There would be prayers over the wine and the bread, and then the game would start. Not the referee’s whistle but something rather similar in a way. I can’t claim that fine wines were drunk, or that the food was even especially good. That, however, isn’t really the point. It’s not the quality of the table but that there was family seated around that table. A people whose recent ancestors had fled pogroms and oppression, who had lost so many in those regular slaughters and then in the genocidal filth of the Shoah, sat in safety and pushed up their cholesterol count along with those they loved and trusted. That was—yes—faith at is finest. Somehow, God knows how, they had survived history. Yes, God did and does know.

Now, half a century later I sit in my large, warm, comfortable Toronto home and consume a much more delicate and subtle meal. Nuance, spices, delicate balances of flavour. And I’m no longer a little boy but a successful journalist and an ordained priest in the Anglican Church. Good Lord that would have surprised them all back then. But made them proud too; well, to be candid, some of them, and some of what I am.

But food is food, and one of the links in the chain of organized goodness and communal kindness is food and family and faith. My grandparents are gone now of course, as are my parents, and their siblings—even my dad’s brother who played for Tottenham reserves. Gone but not forgotten in my 60s memory and in my 60s love. “Let the boy eat,” my grandma used to say about me to my dad. Yes, let us all eat. It’s a matter of faith. Thank God.

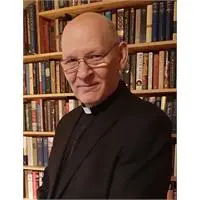

The Reverend Michael Coren is the author of 20 books, several of them best-sellers, translated into a dozen languages. He hosted daily radio and TV shows for almost 20 years, and is now a Contributing Columnist for the Toronto Star, and appears regularly in the Globe and Mail, The Times, Daily Telegraph, Church Times, and numerous other publications in Canada and Britain. He has won numerous award and prizes across North America. He is a priest at St. Luke’s, Burlington. His latest book is Heaping Coals. His website is michaelcoren.com

[email protected]Keep on reading

Resurrection of Hope in Thundering Waters

Of Pancakes and Ashes

Into the Desert with Christ: Why Lent Still Matters in a Frantic and Fractured World

YLTP Registration Now Open Calling All Young Leaders of Niagara!

Every Day is Christmas: Finding Grace in the Midst of War

The Grandparents Club: A New Faith Formation Resource for Churches