Earlier this year playing cricket in, of all things, an Anglican cricket tournament, I pulled my right hamstring. Never happened before—wasn’t even aware I had a hamstring! As I limped off the pitch it suddenly occurred to me that I was old. Not that only old people pull hamstrings but for some strange reason my sense of immortality and perennial youthfulness was as shattered as my cricketing career. I felt the same sort of emotion about writing my memoir. Surely this is usually an old person’s game. Well yes, it is. And Michael, you now qualify.

After decades of writing books about other people, mostly long dead, I now write about myself, not yet dead. What a curious, slightly disturbing feeling it is. Not that it’s the final book, and I just signed a contract for another, but it’s in some ways a last word on my life and that calls for often sobering reflection.

One of the central themes, perhaps the most central theme, of the book is the journey towards ordination. It is, I suppose, a spiritual autobiography. Paradoxically, becoming a priest wasn’t a consideration for most of my life, not even a remote possibility, but as I wrote the book I realised how if I looked behind the curtain of the days, dates, and drama there was that emerging pattern of something almost inevitable. Where would I find meaning, what am I about, what is it that genuinely matters?

But oh, what a circuitous route. A secular, half-Jewish, working-class family and upbringing, clever but lazy, a fully-funded university education, drugs, parties, and irresponsibility, and then a career in journalism, partly because I’d no idea what else to do. Working with Oscar-winning screenwriters, hanging out with Salman Rushdie and Martin Amis, writing books with famous broadcasters, appearing on radio and television, and being published by one of the most respected companies in Britain.

All this by my mid-20s, and the emerging realisation that I was no happier than I’d been before it all. That stung, that made me think, that pushed me towards faith. Then meeting and falling in love with a Canadian, emigrating with no thought for how that hurt my friends and family in England, and 20 years of radio, television, books, and column-writing, often on the conservative wing of politics.

Then a conversion to a faith I’d never known before, something deep and progressive and fulfilling and challenging. That conversion, that slide into ordination, came at such a price and cost, both professional and personal, but it released my soul, revealed the inner workings, and made me the Christian I always ought to have been. It was cathartic and liberating but it was also painful and disturbing. Being forced to ask questions about my own life, and my own being. To be critical and honest. I knew that I’d said and written things over the years that demanded redress and contrition, and for more than a decade have done all in my power to repair and reform. But as I reflected on my life, I thought about how I’d treated those people who loved me and cared for me. I found myself sitting at my desk before dawn—I’ve an eccentric writing schedule —close to tears, even openly weeping, and my own behavior regarding my parents in particular. They’re gone, I can’t call and chat, can only stew in my own regret. That, of course, is what prayer is for, that’s what self-reflection is for. We’ve all made mistakes, none of us perfect. Yet I’m still on that path of self-forgiveness and not sure if I’ll ever reach the end. Not entirely sure I’m supposed to.

The solace I find is in Christ. There, I’ve said it. In Him, in Him alone. Does that make me sound rather evangelical? If so, I rejoice in it. The longer I spend as a priest, the more I realize that there’s a lot of window-dressing around in the church, and there’s a terrible danger of losing the gift among the decorations. What gets me through, what makes it all possible, is the Word made flesh, the Son of God. 65 years of life, recorded in an autobiography, given a central thread by being a follower of Christ and being ordained as a priest. I’m so glad that I wrote this book but just as happy that I won’t have to do it again.

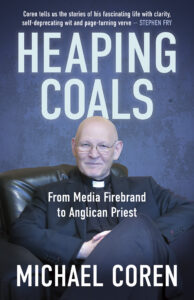

Michael Coren’s memoir, Heaping Coals: From Media Firebrand to Anglican Priest,

has just been published and is widely available at booksellers across the diocese and online

Hamstrings and Memoirs: Piercing the Veil of Immortality

Earlier this year playing cricket in, of all things, an Anglican cricket tournament, I pulled my right hamstring. Never happened before—wasn’t even aware I had a hamstring! As I limped off the pitch it suddenly occurred to me that I was old. Not that only old people pull hamstrings but for some strange reason my sense of immortality and perennial youthfulness was as shattered as my cricketing career. I felt the same sort of emotion about writing my memoir. Surely this is usually an old person’s game. Well yes, it is. And Michael, you now qualify.

After decades of writing books about other people, mostly long dead, I now write about myself, not yet dead. What a curious, slightly disturbing feeling it is. Not that it’s the final book, and I just signed a contract for another, but it’s in some ways a last word on my life and that calls for often sobering reflection.

One of the central themes, perhaps the most central theme, of the book is the journey towards ordination. It is, I suppose, a spiritual autobiography. Paradoxically, becoming a priest wasn’t a consideration for most of my life, not even a remote possibility, but as I wrote the book I realised how if I looked behind the curtain of the days, dates, and drama there was that emerging pattern of something almost inevitable. Where would I find meaning, what am I about, what is it that genuinely matters?

But oh, what a circuitous route. A secular, half-Jewish, working-class family and upbringing, clever but lazy, a fully-funded university education, drugs, parties, and irresponsibility, and then a career in journalism, partly because I’d no idea what else to do. Working with Oscar-winning screenwriters, hanging out with Salman Rushdie and Martin Amis, writing books with famous broadcasters, appearing on radio and television, and being published by one of the most respected companies in Britain.

All this by my mid-20s, and the emerging realisation that I was no happier than I’d been before it all. That stung, that made me think, that pushed me towards faith. Then meeting and falling in love with a Canadian, emigrating with no thought for how that hurt my friends and family in England, and 20 years of radio, television, books, and column-writing, often on the conservative wing of politics.

Then a conversion to a faith I’d never known before, something deep and progressive and fulfilling and challenging. That conversion, that slide into ordination, came at such a price and cost, both professional and personal, but it released my soul, revealed the inner workings, and made me the Christian I always ought to have been. It was cathartic and liberating but it was also painful and disturbing. Being forced to ask questions about my own life, and my own being. To be critical and honest. I knew that I’d said and written things over the years that demanded redress and contrition, and for more than a decade have done all in my power to repair and reform. But as I reflected on my life, I thought about how I’d treated those people who loved me and cared for me. I found myself sitting at my desk before dawn—I’ve an eccentric writing schedule —close to tears, even openly weeping, and my own behavior regarding my parents in particular. They’re gone, I can’t call and chat, can only stew in my own regret. That, of course, is what prayer is for, that’s what self-reflection is for. We’ve all made mistakes, none of us perfect. Yet I’m still on that path of self-forgiveness and not sure if I’ll ever reach the end. Not entirely sure I’m supposed to.

The solace I find is in Christ. There, I’ve said it. In Him, in Him alone. Does that make me sound rather evangelical? If so, I rejoice in it. The longer I spend as a priest, the more I realize that there’s a lot of window-dressing around in the church, and there’s a terrible danger of losing the gift among the decorations. What gets me through, what makes it all possible, is the Word made flesh, the Son of God. 65 years of life, recorded in an autobiography, given a central thread by being a follower of Christ and being ordained as a priest. I’m so glad that I wrote this book but just as happy that I won’t have to do it again.

Michael Coren’s memoir, Heaping Coals: From Media Firebrand to Anglican Priest,

has just been published and is widely available at booksellers across the diocese and online

The Reverend Michael Coren is the author of 20 books, several of them best-sellers, translated into a dozen languages. He hosted daily radio and TV shows for almost 20 years, and is now a Contributing Columnist for the Toronto Star, and appears regularly in the Globe and Mail, The Times, Daily Telegraph, Church Times, and numerous other publications in Canada and Britain. He has won numerous award and prizes across North America. He is a priest at St. Luke’s, Burlington. His latest book is Heaping Coals. His website is michaelcoren.com

[email protected]Keep on reading

Healthy Evangelism: What Does it Look Like? Part 3

A Place to Thrive: Faith, Partnership and the Completion of 412 Barton

Our Treasures and Us: A Time for Reflection

The Slow Process of Belonging

New Window Dedicated at St. Luke’s, Smithville

Remembering Nicodemus